Assessment happens in an ongoing way when using inquiry. In inquiry-based learning, the educator assesses the curriculum expectations from the Health and Physical Education curriculum, integrating the process and the product of the inquiry where applicable, always planning based on curriculum. In inquiry-based learning the process of inquiry is just as important as the final product. Students learn and demonstrate different skills in each of the stages of the inquiry process and it is these skills that can be assessed when they are specifically connected to curriculum expectations.

Learning is enhanced when students are offered multiple ways to demonstrate their learning, because the educator is given more opportunities to understand students’ thinking and learning. Educators can use various ways to collect assessment information about student learning, including a variety of observations, conversations and products such as the following (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2010):

- Formal and informal observations

- Discussions, learning conversations, questioning, conferences

- Tasks done in groups

- Demonstrations, performances

- Projects, portfolios

- Peer and self-assessments

- Self-reflections

For additional assessment tools within the context of Health and Physical Education inquiry refer to the Assessment Tools.

Educators need to plan for the various types of assessment when designing inquiry activities. Assessment can be summarized in three forms: assessment for learning, assessment as learning, and assessment of learning.

The purpose of both assessment for learning and assessment as learning is to improve student learning and inform educator instruction. By looking at evidence and seeing how students are doing—which skills they have learned and where they need further support—educators are able to adjust or differentiate their instruction accordingly and provide specific feedback to help students achieve greater success in their learning.

Assessment of learning involves giving a value to student work related to the curriculum expectations at a given point in time (both at end of each stage and at the end of inquiry) and assigning a grade.

Inquiry-based learning is “clearly weighted in favour of assessment for and as learning since these types of assessments are effective aids for deepening students’ understanding and encouraging student involvement in the learning and assessment process” (The Laboratory School, 2011).

Figure 6: Forms of Assessment in Inquiry-Based Learning

| For | As | Of |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Key Considerations for Assessing Inquiry

When planning assessment opportunities using an inquiry-based learning approach, educators should consider the following concepts from Growing Success (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2010):

- Planning: Assessment should be planned at the same time as instruction, and it should be integrated seamlessly into the learning cycle. Planned assessment should be used to inform instruction, guide next steps, and help both educators and students monitor progress towards achieving learning goals.

- Criteria: Established criteria for assessment and evaluation should be shared with students or co-constructed with students prior to learning. Students’ work should be referenced for assessment and evaluation purposes to established criteria, rather than by comparison with work done by other students.

- Ongoing Assessment: Assessments should be ongoing throughout the learning cycle, varied in nature, and administered over a period of time. Students should be provided with multiple opportunities to demonstrate the full range of their learning throughout the class/course.

- Assessment in inquiry can be used:

- to inform instruction, guide next steps, and help students monitor their progress towards achieving their learning goals

- to give and receive specific and timely descriptive feedback about student learning, and

- to help students to develop skills of peer assessment and self-assessment.

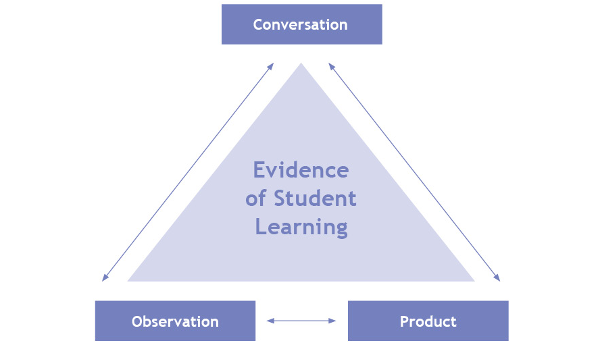

When educators use a variety of sources of evidence the reliability and validity of the evaluation of student learning is increased. To ensure valid and reliable assessment and evaluation, educators are encouraged to collect evidence of student learning from a variety of sources (Figures 7 and 8), on an ongoing basis, and in a variety of settings. Sources can include conversations, observations, and products, collectively referred to as “triangulation of evidence” (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Triangulation of Evidence (Adapted from Ontario Ministry of Education, 2010a)

Figure 8: Sources of Evidence, Considerations and Health and Physical Education Examples

| Examples | Between Peers, With Educator |

|---|---|

| Considerations | Conversations can also include written evidence such as journals in which educators can read what students have to say about their learning rather than listening. |

| H&PE Example | A student is using TGfU and is responding through reflective questions to consider how a game can be adjusted to be more challenging. The educator has a conversation with the student to assess the student’s thinking. |

| Examples | Anecdotal Notes, Assessment Checklists |

|---|---|

| Considerations | Inquiry-based learning involves student collaboration. During times when students are working in pairs or small groups, the educator listens to and observes what students are saying and doing. The educator records observations to help assess what the student knows and is able to do. |

| H&PE Example | Students work in small groups to co-construct qualities (criteria) of a personal fitness goal. The educator moves throughout the room observing student conversations, recording students’ demonstrated knowledge and making anecdotal notes. |

| Examples | Student Work, Student Thinking Recorded |

|---|---|

| Considerations | Inquiry journals, blogs, and portfolios are sources of evidence that reveal growth and progress of student learning over time. |

| H&PE Example | A student shares their inquiry findings related to making healthier food choices when eating out in their community, in a blog post. |

“Documenting students’ questions can provide educators with information about a student’s understanding of the content area at hand, as well as his or her level of critical thinking” (The Laboratory School, 2011, p. 23)

Planning for Assessment

Assessment should be planned prior to beginning an inquiry. Educators can start by assessing what students need to know and need to be able to do by the end of the inquiry. To further guide planning, the following should be considered (Alberta Learning, 2004 & Ontario Ministry of Education, 2010):

- Deciding how to monitor and assess student progress on an ongoing basis

- Planning for monitoring and assessment of the expected learning from the curriculum throughout the inquiry process

- Planning for assessment of the final product if applicable

- Planning for co-constructing success criteria with students when developing assessment tools

- Planning differentiated instruction as the need arises

- Planning self-assessment and peer feedback

- Planning for individual work as well as small group collaboration opportunities

Differentiated Instruction and Assessment

Educators who use a variety of oral, written or visual assessments throughout the inquiry process help address the various learning styles of students. This approach can allow them to demonstrate their learning and make their thinking visible according to their individual strengths.

For any students who find it difficult to express their understanding through writing e.g., visual learners, English language learners, educators can consider using illustrations and other visuals such as graphic organizers to provide evidence of student learning. Sometimes what isn’t included in a students’ illustration can be an indicator of what the student may be overlooking or misunderstanding.

Inquiry-based learning can be approached independently, in pairs or small groups. Educators can consider flexible groupings based on interest, topic/question or readiness in terms of inquiry skills.

Educators should use practices and procedures that “relate to the interests, learning styles and preferences, needs, and experiences of all students” and that “support all students, including those with special education needs, those who are learning the language of instruction (English or French) and those who are First Nation, Metis, or Inuit” (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2010a).

Assessment Tools

The following assessment tools can be used to support student learning throughout an inquiry in Health and Physical Education.

References

Adapted from Ontario Ministry of Education (2010a).

Alberta Learning. (2004). Focus on Inquiry: A educator’s guide to implementing inquiry-based learning. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Learning.

Brown’s Basics. (2015). Inquiry cycle recording template. Retrieved from https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Store/Hands-On-Minds-On-Learning

Gregory, K., Cameron, C., & Davies, A. (2011). Knowing what counts: Setting and using criteria (2nd ed.). Courtenay, BC: Connections Publishing.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2010). Growing success: Assessment, evaluation and reporting in Ontario schools, covering grades 1 to 12 (1st ed.). Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/policyfunding/growSuccess.pdf

The Laboratory School at the Dr. Erick Jackman Institute of Child Study. (2011). Natural curiosity: Building children’s understanding of the world through environmental inquiry / A resource for teachers. Oshawa, ON: Maracle Press Ltd.

The Laboratory School at the Dr. Erick Jackman Institute of Child Study, 2011, p. 23.

Wilhelm, J.D., Wilhelm, P.J., & Boas, E. (2009). Inquiring minds learn to read and write: 50 problem-based literacy and learning strategies. Markham, ON: Scholastic Canada.