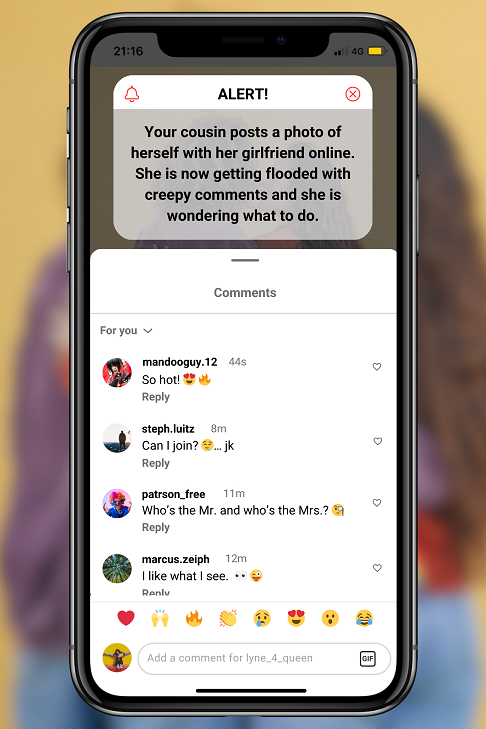

Your cousin posts a photo of herself with her new girlfriend online. She is now getting flooded with creepy comments and she is wondering what to do.

H&PE Curriculum Connections

Grade 7: A1.1, A1.2, A1.4, A1.5, A1.6; D2.2

Grade 8: A1.1, A1.2, A1.4, A1.5, A1.6; D1.5, D2.2, D3.2

Grade 9: 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5; C1.5, C2.2, C3.3

Grade 10: 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, C1.1, C2.3, C3.4

What Is It All About?

Every person is worthy of respect and has the right to live free from discrimination, regardless of their sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression.1

Gender-based violence can affect all people, but it disproportionately affects women, girls, Two Spirit, transgender, nonbinary2 people, and marginalized communities.3 According to Statistics Canada, in Canada, bisexual/pansexual women are more at risk of sexual assault and intimate partner violence than straight or lesbian women.4 Derogatory and homophobic comments are both forms of violence against others, are disrespectful and hurtful, and violate an individual’s human rights and dignity.

Recognizing various types of gender-based violence, both in person and on social media, is key to understanding the factors that can be harmful to an individual’s self-concept, healthy development, and understanding of healthy relationships. Learning about the impact of gender-based violence and developing strategies to respond to situations safely as a bystander leads to safer, more inclusive spaces for all and contributes to a greater appreciation for self and others and respect for the uniqueness of all people.

During this activity, students explore the hypersexualization of romantic relationships between women in an online environment, taking note of the subtleties of this type of gender-based violence. Hypersexualization is the act of attributing sexual overtones to something that is not inherently sexual. The activity encourages students to think about these sexually explicit, derogatory messages (overt and implied) and assess their potential impact on the individuals targeted and those who witness it. Students reflect on attitudes that normalize and diminish the seriousness of this behaviour and explore ways of being a supportive bystander and an advocate for education and change.

The video used for this activity contains two parts.

In part 1 of the video, Julie S. Lalonde addresses:

- What hypersexualization of a relationship is and what it looks like online;

- Why this form of sexual harassment happens and why it is not taken seriously;

- How this form of sexual harassment constitutes gender-based violence both online and in person;

- The impact on the individuals who are targeted;

- Her personal experience of online sexual harassment and the impact it has;

- Victim blaming and rights of all individuals to have a healthy relationship free from sexual harassment.

In Part 2 of the video, Julie speaks to:

- The importance of the role of the bystander and being an ally;

- The impact on different individuals/groups;

- The impact on others who witness it;

- The importance of safely intervening in this form of sexual harassment;

- How to draw the line—strategies for safely and confidently intervening;

- The importance of being an ally to others who experience similar forms of harassment, and to be part of creating a safer world.

What Do We Need?

- Link to Ophea’s Online Sexual Harassment Scenario Video and projection equipment

- Ophea’s Online Sexual Harassment Scenario Card or poster, or a projected copy of the card

- Student Worksheet

- Refer also to Ophea’s Gender-Based Violence Prevention Education Resource Database for additional resources.

Guided Discussion Questions

- How might the hypersexualization of romantic relationships between women impact the way individuals view same-sex relationships (e.g., sexual, taboo, unhealthy, that it’s only done for male attention, attention seeking)?

- How does the hypersexualization of romantic relationships between women impact individuals who are the target of this type of behaviour and others who witness it?

- How does the objectification of individuals that occurs in various online environments reinforce stereotypes/condone inappropriate behaviour (e.g., mainly sexual, taboo, women as sexual objects, perpetuates this type of harassment)?

- How is the hypersexualization of romantic relationships between women a form of online sexual harassment and how does it contribute to gender-based violence (unsolicited comments of a sexual nature are harassment and may lead to other forms of violence)?

- How can this type of online violence be responded to and disrupted safely while supporting the individuals targeted?

- What advice would you give to someone who is being sexually harassed online about their intimate relationship?

Opportunities for Assessment

During the “Minds On,” observe small-group conversation to gather information about students' initial understanding of this form of gender-based violence. Observe their understanding of the subtleties of the overt and implied comments, the attitudes that normalize/diminish the seriousness of this form of harassment, and the potential impact on the individuals targeted and those who witness it.

During the “Action,” use students’ responses on the Student Worksheet and the large group sharing to continue to assess their developing understanding of this form of gender-based violence.

During the “Consolidation,” use the Exit Card on the Student Worksheet to assess students' understanding of responses and actions they would feel comfortable and confident taking to respond to the harassment as a bystander and as an ally. Students will also include how they might educate others about this type of online sexual harassment.

How Is It Done?

Minds On

Have students convene in small groups. Introduce the Online Sexual Harassment Scenario Card. Using the Student Worksheet (or a shared document, sticky notes, chart paper, or Graffiti Wall), have groups capture their ideas in response to the following questions:

- What is happening in this situation? (Have students summarize the scenario for comprehension).

- What is the problem with the comments and emojis posted in response to your cousin’s photo? What problematic messages are communicated (e.g., sexual, unwanted, harmful, degrading, objectifying the individuals as sexual objects)?

- What do you think motivates individuals to post these types of comments (e.g., think they are complimentary, think they have a license to post it since the couple shared their status, homophobia, thinking it’s a “joke”)?

- How might these comments and emojis make your cousin and her girlfriend feel about their relationship or their decision to share their relationship status online (e.g., they are not accepted, feel uncomfortable about sharing it, their relationship is unhealthy or wrong, degraded, feel hurt and embarrassed by the comments, regret about sharing their relationship, worried about other violence that might happen to them)?

- How might these comments and emojis affect others who view them (e.g., affect friends and family, stop others from being more open/sharing their relationship status of a similar nature, affect their decision to come out, feel unsafe, impact how they see themselves, affect how other’s view relationships and an individual’s rights to self-expression, self-concept, self-confidence, self-image, self-worth)?

- What are some of the consequences of engaging in this type of online behaviour or not responding to this type of behaviour (e.g., condones the behaviour as appropriate, silence contributes to the harm being done, creates an unhealthy and unsafe online environment, impacts how others might view the individual who posted the comment, creates a culture of fear of self-expression, elicits fear in others who may feel the same but may not have yet shared their relationship status)?

Action

Access Part 1 of the Online Sexual Harassment Scenario Video.

- As the video plays, encourage students to take notes in the section provided on their worksheet to extend their initial responses to the scenario and learn about how hypersexualizing romantic relationships between women is a form of online sexual harassment. After playing Part 1 of the video, have students review their initial responses to the scenario and add any new ideas/information they learned from the video.

- Have students use their initial responses to the scenario and notes from Part 1 of the video to create three probing questions they would ask their cousin to understand more about how she and her girlfriend are feeling and how to support them (e.g., “I saw your post online, and I am happy for you. How are you both? How can I support you?”). Have groups generate some supportive phrases and actions they might take to help their cousin decide how to respond to the harassment.

- Have groups share some or all of their questions/responses with the class. This will help clarify or extend their thinking about how this form of harassment impacts the individuals targeted, others who witness it, and ways of responding.

Access Part 2 of the Online Sexual Harassment Scenario Video.

- Continue to encourage students to take notes in the section provided on their worksheet as the video plays.

- Have students pay attention to the importance of the role of the bystander as a supportive, trusting friend and the various ways they might safely, comfortably and confidently support their cousin. As well, highlight the importance of maintaining a culture of consent and how to be an ally to others who experience this form of online sexual harassment.

Consolidation

Have students work in their groups using what they learned from Part 2 of the video to complete the Exit Card on the Student Worksheet. Students will refine/add to their possible responses to reassure their cousin, to let them know they support them, and describe the various ways they may respond to the situation.

Have groups consider the actions they would feel comfortable and confident taking to support their cousin in responding to the online sexual harassment. Have groups think about actions they might take as a bystander and as an ally, and how they might educate others about this type of online sexual harassment.

Encourage students to anchor their responses to their understanding of the impact of the hypersexualization of romantic female relationships as a form of sexual harassment, the importance of intervening safely as a bystander, the concept of a consent-based culture, and being an ally to others who experience similar forms of harassment.

Ideas for Extension

Before the activity, review the IDEAL Decision-Making Model with students. This will help to guide their thinking about possible pros and cons and actions they can take to support their cousin, as well as how to be an ally to others who experience this form of online sexual harassment. This framework includes five steps:

- I – Identify the problem.

- D – Describe all possible solutions.

- E – Evaluate the pros and cons of each solution.

- A – Act on the best solution.

- L – Learn from the choices.

Create opportunities to explore the factors that impact an individual’s self-concept, self-awareness, sense of identity, and self-worth, making connections to how these factors are impacted by environments which cultivate diversity, inclusion, respect for self and others, and consent. Have students discuss the characteristics of healthy relationships and what they look like, sound like, and feel like. Invite students to create/draw/find images that represent what they want in a healthy relationship.

Access Ophea’s PlaySport Intermediate/Senior Activities to explore the Pause for Learning open-ended questions, which help cultivate collaboration, conflict-resolution skills, and consideration of other perspectives.

Engage students in further learning with additional Gender-Based Violence Prevention Education Activities.

Explore additional expert videos from Ophea's Gender-Based Violence Prevention suite for support in using the classroom activities with students, such as Introduction to Gender-Based Violence Prevention or Introduction to Consent, to extend discussions about taking action.

Educator Notes

- Before starting a classroom conversation, be aware that some students may have experienced situations related to the topic, either directly or indirectly, in the past or present. This awareness includes recognizing that some students might have already experienced homophobic bullying or harassment and other forms of gender-based violence. Therefore, it is important to identify resources for support that you can share discreetly or generally with students to let them know that they are not alone and that there is always someone who can help them (e.g., trusted adult, educator, guidance counsellor, social worker, social services, health nurse, and/or school liaison officer).

- Coordinate with school support staff (e.g., school guidance counsellor, social worker, principal) to ensure they are aware and available to support or refer students, if needed, during and after the discussion.

- Allow students to capture their feelings in various ways (e.g., notes, pictures, doodles, drawings). Understand that students might have a lot of different emotions in reaction to this scenario. Help students unpack the feelings that come up and work through them in a healthy way.

- Before, during, and after the activity, remind students about the applicable Better and Best Tips. (Refer to Tips for Constructive Classroom Conversations)

- We each have a responsibility to protect children and youth from harm. As a professional educator working directly with students and supporting others doing the same, you have a duty to report when you have reasonable grounds to suspect that a child is or may be in need of protection.

1The Ontario Curriculum, Grades 1–8: Health and Physical Education, 2019, p. 282

2Egale, 2SLBTQI Terms and Definitions, 2024. https://egale.ca/awareness/terms-and-definitions/

3Candian Women’s Foundation: The Facts about Gender-Based Violence, 2024. Extracted from: https://canadianwomen.org/the-facts/gender-based-violence/#:~:text=The%20United%20Nations%20says%2C%20%E2%80%9Cgender,%2C%20and%20non%2Dbinary%20people.

4Statistics Canada, 2021. www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2021001/article/00005-eng.htm