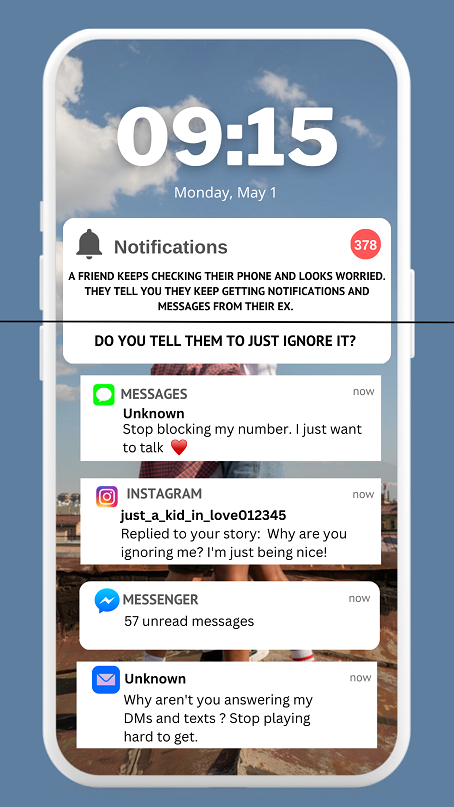

A friend keeps checking their phone and looks worried. They tell you they keep getting notifications and messages from their ex. Do you tell them to just ignore it?

H&PE Curriculum Connections

Grade 7: A1.1, A1.2, A1.4, A1.5, A.16, D1.1, D2.2

Grade 8: A1.1, A1.2, A1.4, A1.5, A 1.6, D2.2, D3.2, D3.3

Grade 9: 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, C1.2, C2.2, C3.2, C3.3

Grade 10: 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, C1.1, C2.3, C2.5, C3.4

What Is It All About?

Knowing how to establish and maintain healthy boundaries in any intimate relationship, recognizing the feelings and challenges involved in ending a relationship, and respecting an individual’s choice to end a relationship are key to developing an understanding of healthy relationships. Students must be able to recognize red flags that could indicate that they, or someone they care about, is experiencing intimate partner violence both online and in person. Students should then be able to respond safely as bystanders.

During this activity, students explore the feelings of the person in this scenario, taking note of the subtleties of the type of intimate partner violence such as stalking that can occur online and in person. The activity encourages students to think about media messages that normalize stalking behaviours as they determine strategies for establishing, communicating, and respecting boundaries in intimate relationships and dealing with intimate partner violence. Students consider the importance of taking responsibility for managing their own emotions and actions in a relationship and explore ways of being a supportive bystander and an advocate for education and change.

The video used for this activity contains two parts.

In part 1 of the video, Julie Lalonde addresses:

- The definition of stalking, including how the legal term in Canada is criminal harassment;

- How all forms of stalking are violent - both online and in person;

- How stalking can occur online, what it looks like, and how it is often dismissed and not viewed as serious;

- Some root causes behind stalking, such as the conflation of stalking behaviours with romance, the idea that no means try harder, and the persistence myth;

- The impact on the individual who is being stalked;

- When we take these situations lightly, we support an unhealthy and potentially threatening environment.

In Part 2 of the video, Julie summarizes key lessons from Ophea’s Partner Stalking scenario.

- Speaks to personal experience of stalking at a young age and impact it had;

- Women and people in bad relationships are often blamed and persecuted;

- Importance of setting and reinforcing boundaries and understanding that no one ever owes anyone anything;

- Everyone is responsible for dealing with their own emotions and actions when an intimate relationship doesn't become or continue as they want it to be.

- Consent Culture and reinforcing that healthy relationships are centered around consent and respect, including setting and respecting boundaries.

- If your friend is being stalked or harassed :

- Support and believe them: Listen to their experience and validate their feelings.

- Check in with your friend: "Are you ok? Let’s talk to someone."

- Be honest : If you’re worried about your friend’s safety, report it to someone you both trust - a caregiver, a teacher, an elder, etc.

- Call it Out : Challenge the myth that it’s just awkwardness, puppy love, etc. If your friend is pursuing someone who is clearly not interested, call them out and tell them why it’s harmful.

What Do We Need?

- Link to Ophea’s Intimate Partner Stalking video and projection equipment

- Ophea’s Intimate Partner Stalking card or poster, or a projected copy of the card

- Media examples of a romantic pursuit of a love interest despite rejection.

- Chart paper or shared electronic document

- Student Worksheet

- See also Ophea’s Gender-Based Violence Prevention Education Resource Database for additional resources.

Guided discussion questions

- How might media messages, myths and norms related to sexual activity impact the way individuals view what is appropriate behavior in a relationship?

- What are some common misconceptions about sexuality in our culture, and how might these misconceptions cause harm to people?

- How can these misconceptions be responded to critically and fairly?

- How do you build healthy relationships, including intimate relationships?

- If someone is being abusive online or in person,what can you do to protect yourself?

- Intimate relationships end for a variety of reasons. What advice would you give to someone who won’t accept that a relationship has ended?

How Is It Done?

Minds On

Have students convene in small groups. Introduce the Intimate Partner Stalking Scenario Card. Using the Student Worksheet ( or a shared document, sticky notes, chart paper, Graffiti Wall) have groups capture their ideas in response to the following questions:

- What might be happening in this situation?

- Why might your friend be worried? What else might your friend be feeling about the situation?

- What are some of the pros and cons of your friend ignoring the situation?

- After considering the pros and cons of ignoring the situation, what would you advise your friend to do?

Post the term” Stalking” for students to reference. Using the Student Worksheet, have groups generate ideas of what constitutes stalking and it might look like and sound like in-person and/ or online.

Have groups share some or all of their responses with the class, to help clarify or extend their thinking of stalking.

Action

Watch Part 1 of the Intimate Partner Stalking Scenario Video. Encourage students to take notes in the section provided on their worksheet as they listen to Julie to extend their initial responses to the scenario and learn about stalking as a form of intimate partner violence.

Have students use their responses to the Intimate Partner Stalking scenario and notes from part 1 of the video to create 3 probing questions they would ask their friend to understand more about the situation and to support their friend.

Introduce the following Graduation scenario. Using the worksheet, have groups generate responses to the questions:

Graduation Scenario:

It is the end of the year and your friend has now decided to move away to attend school. At the graduation, as your friend crosses the stage to receive their diploma, their ex approaches the stage with a bouquet of flowers and in a loud voice, declares their love and asks that they stay together despite the impending physical distance.

- What might your friend be feeling about this public gesture of love?

- What do you think her reaction might be to her ex as a result of this gesture?

- What might this situation look like to others who are witnessing this event?

- Where do you think people learn stalking behaviours?

Have groups share some or all of their responses with the class, to continue to help clarify or extend their thinking of stalking.

Using a large group discussion format, have students identify examples depicted in pop culture, movies or songs about someone pursuing a love interest who is not interested or has rejected them or provide students with examples. Using these examples and the worksheet have groups respond to the questions:

- What messages do these examples communicate about pursuing a love interest despite being rejected?

- How might these types of media messages impact the way individuals view what is appropriate behavior in a relationship?

- Do these examples reinforce stalking-like behavior as a romantic pursuit to gain another person’s attention? Why or why not?

Facilitate a large group discussion using the following question prompt: “Recall what you have learned about consent. In what ways do the relationship behaviours exhibited in the Intimate Partner Violence Scenario, the Graduation scenario and the pop culture examples violate a person's right to consent?

Watch Part 2 of the Intimate Partner Stalking scenario Video. Encourage students to take notes in the section provided on their worksheet as they listen to Julie. Have students pay attention to the influence of media messages on normalizing stalking behavior as romantic, stalking behaviours as a red flag for intimate partner violence, the importance of individuals taking responsibility for their feelings of rejection, respecting each other’s boundaries, and the role of the bystander as a supportive, trusting friend.

Consolidation

Have students work in their groups, using what they learned from watching Part 2 of the video to generate ideas about actions they might take to support their friend in dealing with the online and in person stalking by their ex. Have groups consider what they would say to reassure their friend and let them know you support them, what actions they would advise their friend to take and what actions they might take to help their friend deal with the situation safely. Encourage students to anchor their responses to their understanding of stalking as a form of intimate partner violence, the importance of taking responsibility for one’s own emotions in a relationship, establishing, and respecting boundaries in intimate relationships, and consent.

Next, have groups consider actions they might take as part of the bystander effect and to help create a culture of consent in their school and/ or community. Encourage students to identify trusted adults they would turn to for support with this situation and as adult allies in creating a culture of consent and educating others about stalking.

Ideas for Extension

Before the activity: Review the IDEAL Decision-making Model with students to guide their thinking about possible pros and cons and actions. This framework includes five steps:

- I – Identify the problem.

- D – Describe all possible solutions.

- E – Evaluate the pros and cons of each solution.

- A – Act on the best solution.

- L – Learn from the choices.

Review strategies for regulating emotions, encouraging others to take responsibility for their emotions and actions, establishing, communicating and respecting boundaries in intimate partner relationships, and ways of being a supportive friend.

Have conversations about what respect and consent looks like in a variety of relationships (e.g., sibling, partner, friend). Have students discuss what these relationships look like, sound like, and feel like.

Engage students in further learning about gender-based violence prevention with additional Gender-Based Violence Prevention Education Activities.

Watch additional Draw the Line videos, such as Introduction to Gender-Based Violence Prevention or Introduction to Consent, to extend discussions about taking action.

Educator Notes

- Before starting a classroom conversation, be aware that some students may have experienced situations related to the topic, either directly or indirectly, in the past or present. This includes recognizing that some students might have already experienced intimate partner violence in the form of stalking. Therefore, it is important to identify resources for support that you can share discreetly or generally with students to let them know that they are not alone and that there is always someone who can help them (i.e., trusted adult, educator, guidance counsellor, social worker, social services, health nurse, and/or school liaison officer).

- Ensure students are aware of and can access referral services and resources if they need to. Refer to Ophea’s Gender-Based Violence Prevention Education Resource Database for additional resources.

- Coordinate with school support staff (e.g., school guidance counsellor, social worker, principal) to ensure they are aware and available to support or refer students, if needed, during and after the discussion.

- Allow students to capture their feelings in a variety of ways (notes, pictures, doodles, drawings). Understand that students might have a lot of different feelings in reaction to this scenario. Help students unpack the feelings that come up and work through them in a healthy way.

- Support students with strategies for identifying and managing their emotions in ways that allow them to focus on self-care and their overall well-being.

- Review effective means of communication and how to be assertive.

- Remind students about the Better and Best Tips applicable before, during, and after the activity (refer to Tips for Constructive Classroom Conversations).

- When talking with students about topics that may be closely tied to their personal lives, be sure to make it clear that there are limitations to teacher–student confidentiality. Educators have a responsibility to protect children and youth from harm. If a student’s comments raise questions or concerns, educators should talk with that student individually at an appropriate time. Understanding the context of the information shared is a crucial step in determining what action the educator needs to take. If a student discloses that they are at risk of harm this information cannot remain confidential between only the student and educator. As a professional educator working directly with students and supporting others doing the same, when you have reasonable grounds to suspect that a child is or may be in need of protection you have a duty to report this information without delay to the Children’s Aid Society. Educators should seek support from their administrator to fulfill their duty to report.