It’s our pleasure to share the Ophea platform with Dr. Debbie Donsky.

Debbie is committed to equity and inclusive education where student voice, partnering with communities and empowering teachers leads to the best outcomes for all learners by building learning communities where all voices are valued. Debbie is a Superintendent of Education in the Toronto District School Board, and through collaborative learning spaces, informed by current research, and amplified by technology and social media; she has influenced school improvement at the local, system, and provincial levels.

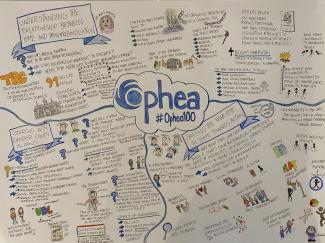

We reached out to Debbie for support in helping to capture the key themes, ideas, and questions that came out of our #Ophea100 Learning Series (a series where we collaborated with subject matter experts to host discussions on topics such as gender equity, understanding the relationship between Physical Education and Truth and Reconciliation, and how to shift the narrative in Health and Physical Education towards action). Check out Debbie's #Ophea100 Learning Series sketchnote for a narrative and graphic interpretation of the journey that the series facilitated, and read on to learn more about Debbie’s experiences as a student that have inspired her work and continued advocacy efforts for inclusive programming.

You can follow her on Twitter @DebbieDonsky and learn more from her website: https://debbiedonsky.com/ and you can also hear directly from her when she joins our Learning for Leaders panel on August 11th! For more information on this upcoming, free, professional learning virtual session and to register visit: Learning for and with Leaders Panel Session.

What if we operated from a space of possibility instead of pathology? What if we centered ability rather than only seeing the deficit lens of limits? What if Health and Physical Education was a space of inclusion, diversity, belonging, risk taking, and celebration?

When Andrea Haefele from Ophea reached out to me to create a sketchnote the irony did not escape me. This is the Ontario Physical and Health Education Association and I am someone who could not wait until I was old enough (grade 10) not to take health and physical education as it has been a site of shame, struggle and trauma for me.

In the fall of 2017 I finally figured out what Brené Brown meant when she said, “If you own this story you get to write the ending”. I stood on a stage in Kitchener and told my story in my TEDx talk, Reclaiming Space.

Instead of the story being about a teacher shaming me in front of my entire grade 8 physical education class, it became about the day that 2000 people gave me a standing ovation. This was the story of a girl who had been shamed, invisibilized, taunted and excluded repeatedly in phys ed class and other spaces for the body she was born with. Instead, the story became about how I stood up for myself, perhaps not with the best choice of language, but certainly having an impact. It became the story of someone who stood there, on a stage, uncomfortable in her own skin, but did it anyway. That evening, of the 2000 people in the audience, 1200 were high school students. My talk was right before intermission and when everyone stood to leave, I came out to see my family and friends who had come to support me. I was swarmed by the students who could not wait to meet me. That was the ending I needed.

In the spaces where body movement is an essential part of the learning–as in physical education classes, those of us who experienced body shaming, body based harassment and outright bullying for the bodies that carry us, can be a challenging space. As I listened to the webinars in the #Ophea100 Learning Series, certain statements resonated and triggered memories - as a young child who began to notice differences, to a child entering into adolescence and noticing changes within myself, as a young woman entering into adulthood, as a grown woman having babies and as an older woman with significant health challenges. As I grew older I came to understand health challenges as a way to dig deeper and come to understand my body–how it works, how it supports me and most of all, how to be grateful for it rather than fight against it.

I think about my love of swimming. I loved to feel the weightlessness of my body and my strength propelling me forward. I recall one summer at overnight camp during the Olympiad - four days of competition - four days of physical expectation that made me want to hide. That year I was in the swim relay. At that camp, the main beach was the center of all activity and everyone was there watching us diving and tagging one another to swim across the length of the docks. It was my turn and when my teammate tagged my hand I pushed off from the edge of the dock and flew through the air until I broke the water and swam as fast as I could. When I got out of the water and walked up the steps to the waiting area, people patted me on the back and asked, “Are you the swimmer?” their tone sounded like both praise and surprise. I found out that I had moved our team from last to first place.

What if we had access to physical activities that complemented our bodies and strengths rather than using it as a tool to ostracize, shame and harm? What if the movements we did to build strength, agility, balance, confidence, power were aligned to our bodies, our abilities, our interests?

What if movement was meaningful and integrated into what our lives required, were nourished by, and taught us how to be strong in different contexts as described in Dr. Janice Forsyth’s webinar on Understanding the Relationship Between Health & Physical Education and Truth and Reconciliation?

I think about sixth grade - baseball season. The most athletic boys were always the captains. One by one they would select their teams and I was always a last round pick. I was a liability. I wasn’t just a girl but a fat girl. I would swing the bat and rarely make contact with the ball. The whole concept evaded me. No one showed me what was wrong. They just waited for me to strike out. The odd time, the good days, the pitcher was off and I would get to walk to first base after 4 balls. I didn’t have to hit the ball and I didn’t have to run in front of everyone. There was no space to learn how to be better at a sport; you were supposed to arrive there already knowing. Many years later, when my own son, Max, was learning how to play baseball, we were playing in the backyard. My husband, Jeff, was pitching to us. Jeff asked, “Why are you hitting right?”. All these years…no one ever considered that I was left handed. Jeff showed me and I hit every single ball after that. Why didn’t my teachers show me that? How would I have felt about myself if someone had said, “turn and face the other way” or “your strength originates differently?”

What if our differences were explored in physical education class rather than seen as a liability? What if our gender did not dictate that we either did dance or strength training? Gymnastics or football? What if what was described in “Starting with Gender Equity in Mind” by Jason Trinh and Joe Tong happened in every physical education class?

As a teacher, I was acutely aware of the importance of ensuring that my physical education class was one where my students would feel included, capable, engaged, proud, strong and part of a team. I taught skills instead of competition. I taught teamwork and turn taking instead of survival of the fittest. I leaned on colleagues for advice and learning so that I could ensure that my intent was the actual experience. One teacher I worked with was also a coach for the York University women’s basketball team and he taught me the skills that you need to have to shoot a basket. He taught me the rules of the game. No longer was the strongest boy always centre. No longer would dodgeball be a secret way to exclude, target, harm and assault. No more did anyone own a particular position on the court or socially.

What if our emotional well-being was central to our engagement in movement so that we could take more risks and embrace vulnerability to learn more about our bodies and how they move? What if teamwork, community, and support for mental health took precedence over winning, hierarchy, and control?

I think about going to my first public protest with my best friend and his son where we challenged the changes to the health curriculum. We were told learning about gender fluidity, gender expression, gender identity, sexual orientation, consent, experiences of body based harassment and assault were being removed from the curriculum. Health was always an opportunity for me to raise my mark because I could study and learn with far more success than I would ever do with the physical component of that class.

What if the curriculum actually taught us about the changes we were experiencing as young children not only physically but emotionally and mentally? What if we spoke openly about the different ways we can experience both gender and sexuality, addressed relationships in meaningful ways, left space for questions that were genuine and encouraged each student to follow the path that their hearts, minds and bodies told them was right for them?

The year following the great shaming I spoke about in the TEDx talk, I had a different experience. The only unit I dreaded more than the running was gymnastics. My body did not move in the ways that other girls’ bodies moved. I could manage the balance beam but never the tumbling. We had to create routines and as many of my classmates took gymnastics and dance outside of school. I would watch as they did cartwheels, walkovers, arials, handsprings and handstands. I would sit on the side hoping not to be noticed but feeling the anxiety of knowing that would never work. One teacher helped me. She explained how I had to move - the body mechanics - the steps - she broke it down and one day, after what felt like an eternity, I did a somersault and for that, I got an A –the first and only time in Phys Ed.

What if asking the question, “What might H&PE look like when it comes from and authentically represents the needs and interests of a highly diverse student population and their communities?” was actually central to teaching, learning and assessment in physical education classrooms as described by Ken Leang, Nicki Keenliside, Milena Trojanovic, Andrea Haefele and Tim Fletcher in Shifting the Narrative in H&PE Towards Action.

What if the importance of designing inclusive spaces, the need for teacher reflection and humility, building trusting relationships and communities, accessibility both physically and socially, having trauma informed practices and understanding the complexities of all of our differences was expected?

What if Health and Physical Education classrooms would create spaces where children would learn not only about how their bodies are strong and capable but that they are strong and capable?

As I move through adulthood and watch my own parents age I have come to understand the joy of movement, the importance of building strength, balance, agility, endurance and power. I can see that treating our bodies with gratitude, curiosity, and respect will help us to age better. I have come to understand that variety - cycling, walking, yoga, meditation, running, balance, dance, social interaction through movement, challenging oneself, and showing appreciation for our bodies are all vital components to a life well-lived.

On that day, on that stage, walking towards the red circle where I would tell my story, weighing more than I ever had in my life, I uttered to myself, “I didn’t trip” and it reverberated throughout the venue. The whole talk was memorized, rehearsed countless times and yet that statement wasn’t planned. In the moment it left my lips I worried – did the audience think I said that because I was fat and therefore uncoordinated? I had said it because my legs felt like jello. I was worried they would give out on me as I walked to centre stage but they did not. They carried me with confidence and I stood there and told the audience that “We need to disrupt these spaces, these voices, these limits and go through the world knowing that not only do we have a right to be here but we have a right to be here out loud and in their face, without apology. And that as we RECLAIM our spaces, we will make the commitment to not make assumptions about someone’s ability, personality, likes or dislikes because of the body that holds them but we will see them as whole people with aspirations and impossible dreams for which they no longer need to ask permission to pursue.”